Modeling

Before we kickstart our first application, let’s have a quick look in what Flow differs from other frameworks.

We claim that Flow lets you concentrate on the essential and in fact this is one major design goal we followed in the making of Flow. There are many factors which can distract developers from their principal task to create an application solving real-world problems. Most of them are infrastructure- related and reappear in almost every project: security, database, validation, persistence, logging, visualization and much more. Flow preaches legible code, well-proven design patterns, true object orientation and provides first class support for Domain-Driven Design. And it takes care of most of the cross-cutting concerns, separating them from the business logic of the application. [1] [2]

Domain-Driven Design

Every software aims to solve problems within its subject area – its domain – for its users. All the product’s other functions are just padding which serves to further this aim. If the domain of your software is the booking of hotel rooms, the reservation and cancellation of rooms are two of your main tasks. However, the presentation of booking forms or the logging of security-relevant occurrences do not belong to the domain ‘hotel room bookings’ and primarily serve to support the main task.

Most of the time it is easy to check whether a function belongs to a domain: imagine that you are booking a room from a receptionist. He is capable of accomplishing the task and will readily meet your request. Now imagine how this employee would react if you asked him to render a booking form or to cache requests. These tasks fall outside his domain. Only in the rarest cases this is the domain of an application ‘software’. Rather most programs offer solutions for real life processes.

To master the complexity of your application it is therefore essential to neatly separate areas which concern the domain from the code and which merely serves the infrastructure. For this you will need a layered architecture – an approach that has worked for decades. Even if you have not previously divided code into layers consciously, the mantra ‘model view controller’ should fall easily from your lips [3] . For the model, which is part of this MVC pattern, is at best a model of part of a domain. As a domain model it is separated from the other applications and resides in its own layer, the domain layer.

Tip

Of course there is much more to say about Domain-Driven Design which doesn’t belong in this tutorial. A good starter is the section about DDD in the Flow documentation.

Domain Model

Our first Flow application will be a blog system. Not because programming blogs is particularly fancy but because you will a) feel instantly at home with the domain and b) it is comparable with tutorials you might know from other frameworks.

So, what does our model look like? Our blog has a number of posts, written by a certain author, with a title, publishing date and the actual post content. Each post can be tagged with an arbitrary number of tags. Finally, visitors of the blog may comment blog posts.

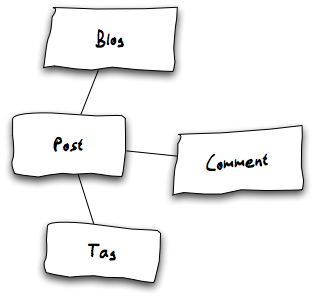

A first sketch shows which domain models (classes) we will need:

A simple model

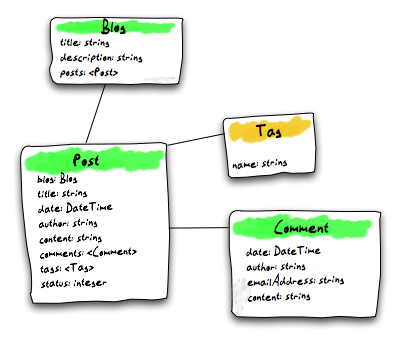

Let’s add some properties to each of the models:

Domain Model with properties

To be honest, the above model is not the best example of a rich Domain Model,

compared to Active Records which usually contain not only properties but also

methods. [4] For simplicity we also defined properties like author as simple

strings – you’d rather plan in a dedicated Author object in a real-world model.

Repositories

Now that you have the models (conceptually) in place, you need to think about

how you will access them. One thing you’ll do is implementing a getter and

setter method for each property you want to be accessible from the outside.

You’ll end up with a lot of methods like getTitle, setAuthor,

addComment and the like [5] . Posts (i.e. Post objects) are stored in

a Blog object in an array or better in an

Doctrine/Common/Collections/Collection [6] instance. For retrieving all posts

from a given Blog all you need to do is calling the getPosts method of the

Blog in question:

$posts = $blog->getPosts();

Executing getComments on the Post would return all related comments:

$comments = $post->getComments();

In the same manner getTags returns all tags attached to a given Post. But

how do you retrieve the active Blog object?

All objects which can’t be found by another object need to be stored in a

repository. In Flow each repository is responsible for exactly one kind of an

object (i.e. one class). Let’s look at the relation between the BlogRepository

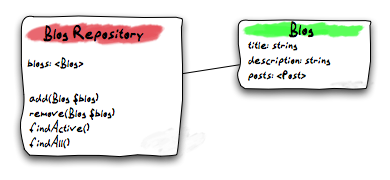

and the Blog:

Blog Repository and Blog

As you see, the BlogRepository provides methods for adding, removing and

finding blogs. In our example application only one blog at a time is supported

so all we need is a function to find the active blog – even though the

repository can contain more than one blog.

Now, what if you want to display a list of the 5 latest posts, no matter what

blog they belong to? One option would be to find all blogs, iterate over their

posts and inspect each date property to create a list of the 5 most recent

posts. Sounds slow? It is.

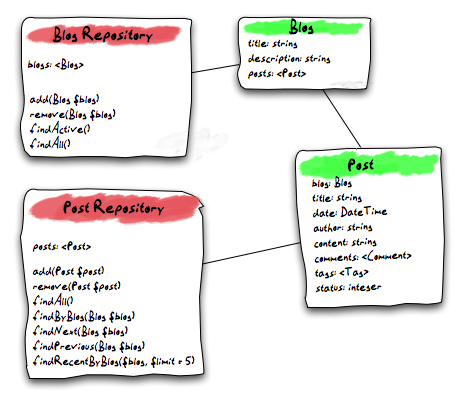

A much better way to find objects by a given criteria is querying a competent

repository. Therefore, if you want to display a list of the 5 latest posts, you

better create a dedicated PostRepository which provides a specialized

findRecentByBlog method:

A dedicated Post Repository

I silently added the findPrevious and findNext methods because you will

later need them for navigating between posts.

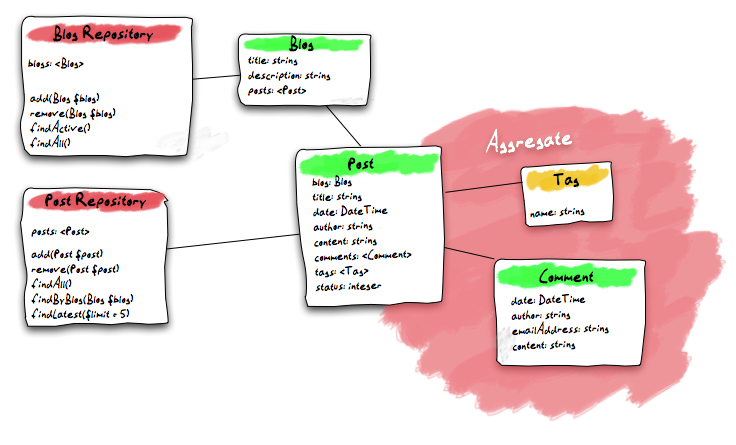

Aggregates

With the Post Repository you’re now able to find posts independently from the Blog. There’s no strict rule for when a model requires its own repository. If you want to display comments independently from their posts and blogs, you’d surely need a Comment Repository, too. In this sample application you can do without it and find the comments you need by calling a getter method on the Post.

All objects which can only be found through a foreign repository, form an

Aggregate. The object having its own repository (in this case Post) becomes

the Aggregate Root:

The Post Aggregate

The concept of aggregates simplifies the overall model because all objects of an aggregate can be seen as a whole: on deleting a post, the framework also deletes all associated comments and tags because it knows that no direct references from outside the aggregate boundary may exist.

Something to keep in mind is the opposite behavior the framework applies, when a repository for an object exists: any changes to it must be registered with that repository, as any persistence cascading of changes stops at aggregate boundaries.

Enough for the modeling part. You’ll surely want some more classes later but first let’s get our hands dirty and start with the actual implementation!